In 1760 James Caulfeild, Viscount Charlemont (he would be created first Earl of Charlemont three years later) wrote in his memoirs, ‘I quickly perceived and being thoroughly sensible it was my indispensable duty to live in Ireland, determined by some means or other to attach myself to my native country: and principally with this view I began those improvements at Marino which have proved so expensive to me.’ Wonderfully situated on rising ground looking south across Dublin Bay and towards the Wicklow Mountains, Marino was Lord Charlemont’s pocket estate just a couple of miles east of Ireland’s capital. At its heart were some 50 acres acquired by his stepfather Thomas Adderley on which the latter built a residence originally called Donnycarney House. This he presented in 1755 to Charlemont on the young man’s return from a Grand Tour lasting no less than nine years during which period, together with time spent in the customary European destinations, he had taken an extended voyage to Greece, Turkey and Egypt.

However, unquestionably the most important country visited by Charlemont was Italy and the painting above, painted in 1773 by Thomas Roberts, Ireland’s finest landscape artist of the 18th century, portrays the kind of arcadian Italianate view first proposed over 100 years before by Claude Lorrain and Poussin, complete with shepherd and flock of sheep. The picture furthermore gives expression to Charlemont’s ambition to improve not only the Marino estate but also the country of which it was part. This is embodied by the building at the heart, if not the actual centre, of the painting: a small temple or casino.

While in Rome during the course of his Grand Tour, Lord Charlemont came to know a number of artists such as Pompeo Batoni, whose wonderful portrait of him can now be found in the Yale Center for British Art. He also associated with Giovanni Piransi, the first four-volume edition of whose Antichitá Romane (1756) was dedicated to his Irish friend, ‘Regni Hiberniae Patricio’ although the two men subsequently quarrelled. But the link to Piranesi demonstrates Charlemont’s interest in architecture from an early age, also evidenced by his commissioning a design for a garden temple from Luigi Vanvitelli, today best-known for the enormous Bourbon palace of Caserta. Vanvitelli’s proposal for an Irish building was rejected on the grounds of expense, but another architect with whom Charlemont first became acquainted while in Rome produced a more satisfactory, if ultimately no less costly, scheme. This was Sir William Chambers, responsible not just for the casino in the grounds of Marino but also Charlemont’s superb townhouse in central Dublin (today the Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art). Despite designing both these buildings and Trinity College’s Chapel and Examination Hall it should be noted that Chambers never came to Ireland.

Work on the casino at Marino was not completed until the mid-1770s perhaps in part because its owner placed many other demands on his income and was therefore constantly short of funds. But even before completion the building’s exceptional merits were recognised, as can be testified by the number of artists who produced paintings in which it features. Aside from Thomas Roberts, there was James Malton whose watercolour dated 1795 is shown above, together with an engraving by Thomas Milton after Francis Wheatley which was produced twelve years before. Jonathan Fisher, James Coy and George Mullins were among those who also exhibited work depicting the casino during the same period. It is difficult to think of any other building, certainly one of the casino’s relatively modest proportions, that attracted as much notice in 18th century Ireland.

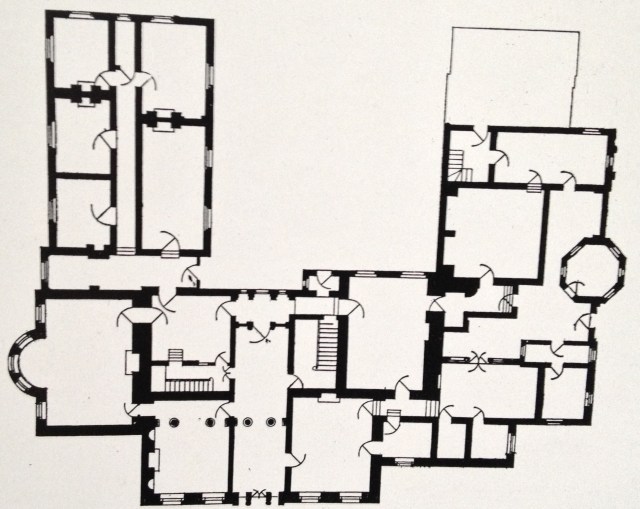

The sublime perfection of the casino at Marino – contained within a elaborately carved Portland stone exterior the Greek Cross plan measures just 40 by 40 feet yet contains 16 rooms spread over three floors, many of them with splendid plasterwork and inlaid floors – has been often described and analysed, and I do not intend to do either here. Less appreciated is the fact that this was just one of a number of ornamental buildings once found on Charlemont’s estate which he gradually extended to three times its original acreage. size. The main residence was Marino House seen above; the early 20th century photograph shows the principal facade behind which were two long wings creating a kind of rear courtyard; the rooms here included an important library and a gallery to accommodate some of the owner’s extensive book, picture and sculpture collection.

We know that Charlemont employed Matthew Peters to help with the design of the parkland at Marino. Born in Belfast, before settling in Dublin in the early 1740s he had worked as a gardener for his uncle who was employed by Lord Cobham at Stowe, Buckinghamshire. Given the influence exerted by Stowe’s park for many years hence, Peters’ presence there as a young man strikes me as highly important in the layout of Marino. In the evolution of garden design during the 18th century from French-style formality to the supposedly natural but carefully planned ‘English garden’ championed by Capability Brown (who also worked at Stowe), a slightly earlier alternative to the former was proposed. Best described as picturesque it is represented today by the likes of Stourhead in Wiltshire and Painshill, Surrey; can it be mere coincidence that the man responsible for the latter’s creation, the Hon Charles Hamilton, was born in Dublin the son of an Irish peer? At Stourhead and Painshill – both of which evolved around the same time as Marino – the park is treated as a series of rooms, each with its own character and focal point. Visiting them is like moving around a gallery holding different but complementary paintings and, I would propose, the same was once also true of Marino with the casino as the finest but by no means the only item meriting visitors’ attention.

So at Marino, Charlemont’s park once held an extensive series of buildings of widely divergent character. We have become so accustomed to the casino as the embodiment of neo-classicism it can come as a shock to discover that not far away on the same estate was a tall Gothic tower known as ‘Rosamund’s Bower.’ Dating from 1762, it stood at the end of a serpentine lake populated by ducks and swans. The tower’s front imitated a ‘highly ornamental screen, adorned with tracery and niches…a crocketed pinnacle conveying the idea of a spire’ while the interior, lit by stained glass windows ‘has been fitted up to imitate a nave, and side aisles of a cathedral.’ Two views of Rosamund’s Bower are shown above. It has been suggested that this structure was designed by Johann Heinrich Muntz, a Swiss-born painter and architect who was encouraged by Horace Walpole to move to England where he worked with Sir William Chambers. Marino House itself contained an ‘Egyptian Room’, so called because of its decoration, while elsewhere in the grounds could be found rustic hermitages, a root house and a moss house, together with such resting points as a covered gothic seat which, in a surviving drawing looks like a much-pinnacled bus shelter. A handful of drawings of the other structures at Marino were made by Thomas Roberts’ younger brother, confusingly called Thomas Sautelle Roberts. Two of them can be seen below and offer us a suggestion of how the grounds of Marino must have looked in the late 18th century.

The greater part of Marino as originally laid out no longer exists, and with it has gone the context in which the casino was intended to be seen and understood. Like so many Irishmen before and since Lord Charlemont spent beyond his means and left his heir heavily in debt. The family never recovered and even by 1835 the Dublin Penny Journal could remark that the estate’s grounds, to which Charlemont had always admitted the public – and in which he was mugged on a number of occasions – had ‘now lost its attraction – it has long been neglected’ while Rosamund’s Bower was ‘in ruins and a stranger seldom visits it.’ Furthermore the estate’s proximity to an expanding city made it vulnerable to encroachment. In the early 1880s the Caulfeilds sold the land to the Christian Brothers who initially occupied Marino House but eventually moved to other buildings put up in the grounds. In the 1920s Dublin Corporation acquired some 90 acres of the former estate and build almost 1,300 houses for local families; it was at this time that Marino House was demolished with almost nothing other than a couple of chimneypieces salvaged. The casino might likewise have been lost but thankfully its importance was recognised: in 1930 the building was taken into state care, the first post-1700 structure to be designated a National Monument. Now standing on just a few acres and surrounded on all sides by buildings of later date and lesser merit, today the casino is looked after by the Office of Public Works and open to the public.

The Casino at Marino is currently hosting an exhibition, The Absent Architect, until the end of April. For more information, see http://www.heritageireland.ie/en/dublin/casinomarino/

Dear Robert Thank you for your post on The Casino which I am sure readers will thoroughly enjoy for the excellent context it gives for the now sole remaining main structure in Charlemont’s Marino Estate. Through The Absent Architect Exhibition we wish to attract greater numbers of visitors to the Casino -‘this most perfect expression of Chambers creativity in small scale design’- and thus grow the numbers of people interested in our 18th century cultural inheritance. There is no charge for admittance to the Exhibition.

Robert – possibly my most favourite building in Europe and worthy to be up there with the greats of Rome and Paris. Lovely article.

Later date and lesser merit , that’s an understatement .

Why is it that we must despise things to almost oblivion before we love them , buildings , art , furniture , literature all appear to undergo this process .

These things are sent to try us while we are on this earth…

I do like Thomas Roberts’s work, so I thank you for the introduction. The casino is a delight, as you say.

Thomas Roberts was without question the most outstanding landscape artist working in Ireland during the 18th century; sadly he died at the age of just 28, so who knows what he might have achieved had he lived longer. There is an outstanding monograph devoted to him, written by William Laffan and Brendan Mooney and published by the Churchill Press in 2009 to coincide with an exhibition of his work at the National Gallery of Ireland. I recommend it to anyone interested in Roberts and indeed in 18th century Irish art.

Robert, wonderful article. Another print for your collection might be the 1874 Croquet Championships, which were held on the grounds of the Casino. There is an image of this in the Casino OPW pamphlet by Sean O’Reilly. Lovely to meet you on Saturday & chat to you soon, Rose Anne

Hmm, I don’t have a copy of Sean O’Reilly’s pamphlet, so must get one to add to my collection. Meanwhile, you might be interested to know that many of the rules according to which croquet is now played were first formulated at a couple of houses in the mid-19th century in this part of County Meath.

http://postimg.org/image/um44p9or1/ -> Hope this loads for you. Yes! Croquet’s real history really turns the modern view of it on its head, doesn’t it! More of an Irish export than a British import etc. The original of the image I uploaded is held by http://www.croquetireland.com/.

Dear Rose Anne,

Thanks for photograph and link to Croquet Association of Ireland website – but I can’t find the picture on that – where is it? Thought to show the pic on my blog as I know it will interest lots of people (and I can mention the importance of Ireland in development of the game).

A pleasure to meet and speak with you on Saturday – please excuse short email, I have just been outdoors in the freezing cold clearing gutters and my hands have lost almost all feeling!

Hi Robert, they don’t have the image on their website at all, what I meant was that they have it physically in their buildings, sorry for the confusion!

That makes more sense. On the other hand, do you have information on where this image came from (there is a fold in the image which suggests it was in a publication of some kind).

It’s possible that that fold line is from the scanner. I just had a quick check in O’Connor (Pleasing Hours), MacCarthy (Circle), and Malins (Demesnes), and the image doesn’t appear in any of those books. The only place I know of it being reproduced is in the Sean O’Reilly pamphlet book (although I would hardly call my search exhaustive!), where it is credited as “The Irish Croquet Championships at the Casino, Marino, 1874 [Croquet Association of Ireland]”. Neither event nor picture are referred to in the text of the pamphlet. I can pop you a copy of the pamphlet in the post no problem.

Don’t worry, I’ll follow it up myself – thanks for image and all the help. I emailed you so if you reply to that on my email, I’ll send you my address for copy of pamphlet when you have a mo.

Great article as always. Love the Casino and good to have an excuse to return. The images chosen are really beautiful throughout (Rosamund’s Bower looks crazy). Lovely to see the Thomas Roberts ones. I have heard of moss houses, being common enough in Wicklow, but root houses?! That’s a new one for me…

Thanks, Michael

Thank you Michael. Actually root houses were not altogether unusual; I am racking my brain trying to recall where else one was found (help anyone?). In those kind of picturesque gardens offering the visitor diversity was important, hence the use of different styles and materials in the buildings.

Dear Robert. I am currently doing a research project on the Casino at Marino and it’s landscape, which explores the changes in the building, gardens and greater surroundings over time. I had been finding it difficult to find details of the garden design so this article is just wonderful.

I would hugely appreciate it if you could let me know of any other resources that you think I would find helpful. You’ve been a huge help already though, so thank-you!

Thank you for your comment and glad to hear you found this useful. It is difficult to know what to suggest since I don’t know what sources you have already consulted. I assume you have read Edward Malins/Knight of Glin book Lost Demesnes? I would also propose that you look at contemporaneous gardens in England, such as the two I mentioned in order to contextualise Marino. The casino needs to be seen as part of a wider and more elaborate parkland, and also as part of a wider movement in the history of garden design. I hope these brief comments are of further help to you.

The croquet image used in the booklet by Sean O’Reilly was used for a card published by the Croquet Association of Ireland. From what I remember I think it was a Christmas card. I found the card and thought it would make a good image for the booklet, making the point of public access to the demesne, but never saw the original image.

Thank you for your comment. Yes, the original of this image seems to be elusive altho’ it has now been reproduced on several occasions. I wonder if anyone knows where it might have first appeared?